George and Veronica Phalen Leadership Academy

An A-Rated School Honoring George and Veronica Phalen

- George and Veronica Phalen Leadership Academy

- George and Veronica Phalen

-

Who Are George and Veronica Phalen?

By the time PLA CEO and Founder Earl Martin Phalen was two years old, the odds of becoming a successful adult were already stacked against him. That’s until he met George and Veronica. They helped prove that long shots make the best stories.

Abandoned at birth in 1967, PLA CEO and Founder, Earl Martin Phalen, could have been another of many African-American children who struggle unsuccessfully through state foster care systems. At that time, Earl would later note, 70 percent of black males in his situation eventually would wind up in the penal system.

But in 1968, the Phalens — George and Veronica — intervened. In their mid-40s, they had a happy home in Norwood, Mass., a blue-collar suburb of Boston. It was a big family with seven kids, the oldest of whom was finishing up at college while another was just heading off to school. The other five were growing up fast, but the Phalens had room for one more child.

"We had always been so involved in the civil rights struggle that we thought that if nothing else, we could adopt a male child. We had a happy home, so we decided to do that," said Veronica. "We started with adoption agencies and got in contact with the Massachusetts Adoption Resource Exchange. One woman saw our request and wanted to make sure it happened. She had fallen in love with Earl. He was the greatest kid. It took a year to go through the system and the faint of heart might not have continued. But it wasn't just some impulse."

A year later, little Earl finally had a home. It was a home that embraced Earl's color rather than looked past it. The Phalens deliberately taught him to have pride in his heritage. That's why he felt free to question his junior high school teacher about Thomas Jefferson, wondering why he was treated as a hero of freedom when he treated Earl's ancestors "like cattle."

"My parents, particularly my mother, helped instill a sense of social justice in me," Earl said last week. "When you think about a white family adopting a black child in the '60s, you realize how important that was to them. They brought a focus and a perspective and a sense of equality to me. Their adopting me was a very intentional decision."

Veronica's parents had emigrated from Ireland and broke local tradition by sending their daughter to public school while others were headed to parochial school. "My parents sent me to public school because they wanted diversity," she said. "That's why they had come here. That was our cup of tea."

Earl grew up in an environment full of love and support. He got good grades, worked hard and gained a reputation as an athlete, although he downplayed his basketball skills at Norwood High. "I was not very good," he said. "I was athletic and a good defender. I thought I was the best defender on the team and I had a strong work ethic. Our teams were very successful, but I wasn't the star by any means."

But he was good enough to draw some attention from Division I scouts and wound up at Yale University, where he earned two varsity letters.

His memories of Yale may not include basketball heroics, but he did begin to have confidence in his journey to discover a way to affect change for other's less fortunate than himself. He found Yale to be an environment that fostered thought and expression with professors and classmates. Earl soaked up the atmosphere and learned lessons both in the classroom and outside it.

More lessons were to come after his 1989 graduation, when he headed south. "In the year between Yale and law school, he spent a whole year volunteering at a homeless shelter with the Lutheran Church in Washington, D.C.," said Veronica. "That put something in his head. We could feel him growing there."

Earl had gotten a taste of working with young people and it was not about to wear off. In his first year of law school at Harvard he was distracted by the thought.

After finishing that first year, Earl went to Jamaica to work on human rights cases — trying to find justice for victims of police brutality and other abuses. But when he returned to Cambridge, he told Professor Charles Ogletree that he wanted to work with children.

"Here was this bright kid,'' Ogletree told the Boston Herald in 2003, "who had graduated from Yale and was attending Harvard Law. But he approached me with this idealistic view of the world and told me that he wanted to save the next generation of inner-city kids. I told him to come back when he was serious."

Earl kept coming back. He landed a job as a teaching assistant at an orphanage, working with children from ages 5 to 18. But when he got there he was told that there was both good news and bad news. "The good news was that I was going to be able to do a lot of teaching," he said. "The bad news was that the assigned teacher had left."

He went from being a completely inexperienced assistant to a completely inexperienced teacher on his first day. By the end of the day, when he saw the face of a 6-year-old light up when she learned how to add, he knew he was hooked. Law school was suddenly in the way. He wanted to quit right then.

"We had been through this before, so we told him that having a law degree was the best basis for anything he wanted to do," said Veronica. "Having a law background prepares you for anything, like starting a business or a foundation."

So Earl stayed at Harvard Law School and continued to tell Ogletree of his idealistic world-saving notions.

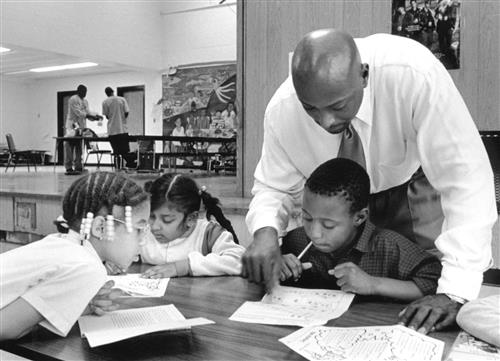

That second year, he and some other black students at the Law School began mentoring children at a community center in Roxbury, a low-income section of Boston. Earl wanted to tell those kids that through education, anything was possible. That their wildest dreams could come true. But then came reality.

The 15-year-old kids they were to tutor were considered among the best at their schools, but most could not even read at a sixth-grade level.

"We were blown away," Earl remembered. "No, it was worse than that. We were sick to our stomachs. These kids weren't getting the basic skills that they needed, and here we were talking about working hard and going to law school and there was nothing in their reality that was pointing in that direction."

Never before had his thoughts been so crystalized. He knew he had to help provide those kids with the opportunities he had been afforded.Earl became Co-Founder and CEO of BELL (building Educated Leaders for Life), a national nonprofit organization that provides evidence-based extended learning programs to students over 14,000 students in underserved communities.

"He never stopped dreaming that way," Veronica said of Earl's plan to enroll 50,000 scholars. "He is such a joy. He clung to his dream. People were always saying, 'Earl, you could do so much with your law degree.' But it fell upon deaf ears."Today, Earl's model has been cited in two recently-filed legislative proposals, one from New York Senator Hillary Clinton and another by Illinois Senator Barack Obama, a friend of Earl's from his Harvard Law School days.

As a result of his adoption by George and Veronica Phalen and their passion for education, Earl beat the odds. He graduated from Yale University and Harvard Law School and has dedicated the past 20 years of his life to expanding the life opportunities of children through learning and academic engagement.

President Clinton awarded Mr. Phalen the President’s Service Award for outstanding community service. He has been named as an "Angel Among Us" by the American Red Cross of Massachusetts Bay. BET honored Earl as a Hero for his work in improving the lives of children. He has earned a Social Capitalist Award from Fast Company magazine as one of the top 25 entrepreneurs solving the world's toughest problems with creativity, ingenuity and passion.After BELL, in 2009, Mr. Phalen founded Summer Advantage USA. The Summer Advantage program is one of only two scientifically proven models in the country and has served more than 15,000 children in five states. It has been recognized by the White House initiative, United We Serve, TIME Magazine and MSNBC. Its research-based summer programs impact the performance of students and school districts.

In 2012, the Indiana Charter School Board granted approval to the George and Veronica Phalen Leadership Academies to open 10 Academies and serve nearly 10,000 students. Named after George and Veronica, the Academies provide students in underserved communities high quality academic programming, enrichment experiences, and a blended learning curriculum that leverages state-of-the-art technology.

Veronica, now 82 years old, couldn't be prouder of her youngest son. "What he's done blows our minds," she said. "I wish we could be around for another 25 years to see it through."The values, the legacy, love and determination that George and Veronica Phalen passed on to Earl Martin Phalen is forever vibrant in the halls of PLA schools and within The George and Veronica Phalen Leadership Academy.

Original Story by Ivy League Black History

-

"The values, the legacy, love and determination that George and Veronica Phalen passed on to Earl Martin Phalen is forever vibrant in the halls of PLA schools and within The George and Veronica Phalen Leadership Academy."